What is Contextualization and Is It Really Biblical?

Contextualization is a term that missiologists, aka teachers about Christian mission, use to describe effective Gospel communication. Basically speaking, this term refers to the Christian communicator's effective expression of the message of God to people of other cultural settings. Underneath this concept resides the intention of creating a specific understanding and response from the listener. The Christian communicator desires that the receptor or listener understand and obey God's will as taught in Scripture, experience personal redemption and transformation, and in turn effectively express that message to others.

We all do contextualization everyday whether we realize it or not. Whether we are a Christian preacher, teacher, evangelist, VBS worker, childcare worker, musician, artist, web designer, or videographer we are communicators with an important message to give to a specific era, subculture, age group, language, or ethnicity. At one given moment we might talk with our three-year-old, and the next minute, we might pick up the phone to talk with our lawyer. We don't use the same vocabulary and tone of voice in both conversations, but we subconsciously switch gears to speak in a way that makes sense for the listener and the topic at hand. In such a case we could say that we have mastered the practice of contextualization, especially if you are a mother with a degree in law. In other contexts, with other kinds of people, we might find ourselves struggling to understand as a listener and express our thoughts as a communicator. Some Christian preachers are deathly afraid of the term, yet at the same time are practicing it every week.

Fear of the concept may stem from misunderstanding, so some basic explanations are necessary to dispel those fears. If we read the Bible with an open mind and heart, we will discover that the Bible itself is a compilation of contextualized books written by authors who desired to communicate to a specific people, in a specific place, at certain point in time, and in an ancient language. Both the medium of Scripture and its message embody and engage in contextualization.

In past decades only a few scholars addressed the topic of contextualization within the medium and message of Scripture. In 1978 missiologist Charles Kraft emphasized the importance of comprehending contextualization on the basis of Scripture, “Contextualization of theology must be biblically based if it is to be Christian” (Charles H. Kraft, ”The Contextualization of Theology,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly, January 1978, 14:36.)

Others have also expressed the need to address contextualization from a biblical perspective. For example, H.D. Beeby notes, “the more we reclaim the Bible as a whole, the more we see the canonical scriptures as providing a missionary mandate, a missionary critique, and a missionary objective” (H.D. Beeby, Canon and Mission, Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1999, 29).

Leading Evangelical Christian scholars have offered many definitions of this difficult concept. Here are a few below with the author's name and sources referenced.

Dean Gilliland

Gilliland defines the meaning of contextualization in theology:

True theology is the attempt on the part of the church to explain and interpret the meaning of the gospel for its own life and to answer questions raised by the Christian faith, using the thought, values, and categories of truth, which are authentic to that place and time.

Source: Dean S. Gilliland, ed. The Word Among Us: Contextualizing Theology for Mission Today. (Dallas, TX: Word Publishing, 1989), 10-11.

David J. Hesselgrave and Edward Rommen

Evangelical missiologists Hesselgrave and Rommen define contextualization as

. . . the attempt to communicate the message of the person, works, Word, and will of God in a way that is faithful to God’s revelation especially as is put forth in the teachings of Holy Scripture, and that is meaningful to respondents in their respective cultural and existential contexts.

Source: David J. Hesselgrave and Edward Rommen, Contextualization: Meanings, Methods, and Models (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2000), 200.

A. Scott Moreau

Steering the term towards a holistic direction, Moreau defines contextualization as

the process whereby Christians adapt the forms, content, and praxis of the Christian faith so as to communicate it to the minds and hearts of people with other cultural backgrounds. The goal is to make the Christian faith as a whole—not only the message but also the means of living out of our faith in the local setting—understandable.

Source: "Contextualization: From an Adapted Message to an Adapted Life, " A. Scott Moreau, in The Changing Face of World Missions, eds. Michael Pocock, Gailyn Van Rheenen, and Douglas McConnell (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 323.

Expanding on the breadth of a holistic contextualization Moreau defines it in a more recent text.

Contextualization happens everywhere the church exists. And by church, I'm referring to the people of God rather than to buildings. Contextualization refers to how these people live out their faith in light of the values of their societies. It is not limited to theology, architecture, church polity, ritual, training, art, or spiritual experience: it includes them all and more.

Source: A. Scott Moreau, Contextualizing the Faith: A Holistic Approach (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2018), 1.

Dean Flemming

I take contextualization, then, to refer to the dynamic and comprehensive process by which the gospel is incarnated within a concrete historical or cultural situation. This happens in such a way that the gospel both comes to authentic expression in the local context and at the same time prophetically transforms the context. Contextualization seeks to enable the people of God to live out the gospel in obedience to Christ within their own cultures and circumstances.

Source: Dean Flemming, Contextualization in the NT: Patterns for Theology and Mission. (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2005), 19.

Jackson Wu

Wu sees the concept as a process involving Scripture and culture, "Good contextualization seeks to be faithful to Scripture and meaningful to a given culture."

Source: Jackson Wu, One Gospel for All Nations: A Practical Approach to Biblical Contextualization (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2015), 8.

To sum up the observations of these scholars we conclude that contextualization is biblical, holistic, dynamic, powerful, meaningful, Spirit-led, and sometimes difficult. To appreciate the beauty of the New Testament as a contextual document one should read and study Dean Flemming's work referenced above, Contextualization in the NT: Patterns for Theology and Mission. Proper contextualization is anchored on the truths of Scripture and is adequately dynamic to address the needs of different cultures. Because God created humanity in his own image and gave us the Scriptures to address the need of humanity's redemption, we can have confidence in the content of the Scriptures to address that need.

At the same time, we should follow the Bible's example of recontextualizing older Scriptures, which sets the precedent for our need to recontextualize God's message. The Scriptures are filled with a plethora of quotations and references to previous Scriptures. Here are a few examples -- numerous OT quotes and metaphors in the NT; the reapplication of the Abrahamic Covenant in the teachings of Jesus, Romans, and Hebrews; the repetition and reapplication of the Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy, the Gospels, and the Epistles. Why are older Scriptures repeated in both the OT and NT? Because God knows that his people of all eras and cultures have universal needs as well as live in unique, dynamically changing contexts. Yes, there is always the danger of over-contextualization or syncretism, but to not engage in contextualization eventually leads to syncretism and meaningless religious practice.

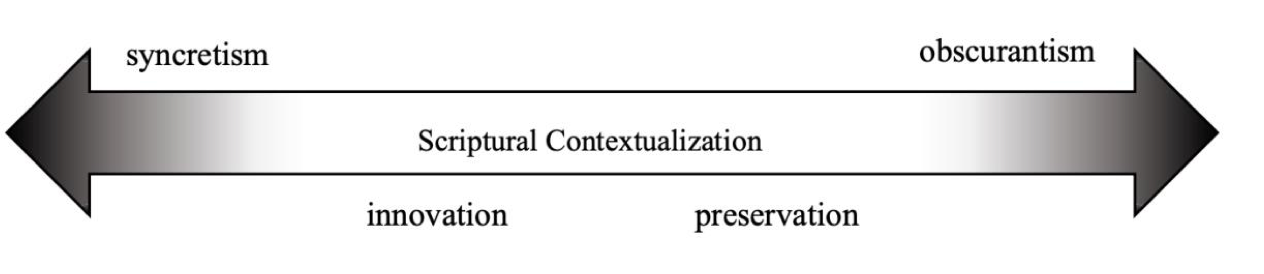

The figure below may help in understanding the concept as a dynamic process.

The gradient two-way arrow depicts the continuum of biblical contextualization. The extremes to avoid are syncretism and obscurantism. Obscurantism occurs when the communicative expressions are so culturally distant or outdated, that disciples and inquirers cannot adequately comprehend certain teachings of the Christian faith. They may better comprehend those teachings if we modify the way we express them. A clear line between the boundaries of syncretism, obscurantism, and biblical contextualization does not always exist.

While cardinal teachings and universal moral values of the faith fall in the middle or white region, some practices may be on the edge or in the fuzzy, grey area of classification, or they have entered the darker extremes on the continuum. Sometimes practices which are obscure or nostalgic may once again become effective tools of biblical communication, especially in times of extreme societal or technological shifts.

The extreme fluidity of contemporary life in a Western culture that values change makes the task of contextualization even more challenging. The condition of liquid modernity intensifies our challenge. By liquid modernity, I mean that we are living in an era that mixes elements and thinking from ancient, modern, and postmodern eras. The numerous works by and about Zygmunt Bauman who popularized the concept explain the idea in greater detail (Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity, 2000). Other factors which contain blessings and challenges include globalization, mass immigration, digital technology, and the abundance of intercultural exchange of ideas and products. The recent Covid-19 pandemic as well as accompanying political polarization have also highlighted the needs and challenges of contextualization. The postmodern idea that power produces knowledge rather than vice versa remains a major issue. Finding balance between the need for both security and freedom will also be a major issue for years to come. While we may not have the answer for every contemporary issue, we do have an anchor in Christ the Living Word as well as in the Scriptures, the written Word. The eternal life-giving Logos, who is Christ possesses the knowledge, power, wisdom, and redemption that all of humanity needs. Only the Logos can provide the contextual message for all people of every age.